International Women's Day is celebrated on March 8th, to commemorate Russian women's winning of the vote in 1917, after organizing a four-day strike that forced the Czar to abdicate. But the first Women's Day observance, called National Woman's Day, was actually held on February 28th, 1909, in New York City, organized by socialist activist Theresa Malkiel, a labor organizer and educator. Today, International Women's Day demonstrations are still largely protests against the oppression and inequality that women are subjected to.

Covers for The First Wife by Paulina Chizianc, One of Us is Sleeping by Josefine Klougart, and The Lying Life of Adults by Elena Ferrante

Covers for The First Wife by Paulina Chizianc, One of Us is Sleeping by Josefine Klougart, and The Lying Life of Adults by Elena Ferrante

► All the words in bold include links. Click them to continue reading! ◄

Women's plight is all-encompassing: this year, women in the Philippines called for labor rights, Turkish women marched against government persecution of demonstrators and protesters, Pakistani women called for an end to street harassment and Mexican women to the violence and murder against women and girls, Argentine women continued to reclaim for the legalization of abortion, and Spanish women protested against xenophobia and prejudice; among many other marches and demonstrations.

Access to literacy and education has long been one of the big fights for women's rights. As of 2015, women still made up two thirds of the world's illiterate population, despite the notorious reduction of the literacy gender gap in the last century. It has been estimated that in the later Middle Ages, only 10 percent of all men and 1 percent of all women were literate. According to Translators through History:

While translation was seen as one of the few socially sanctioned ways of writing open to women during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, (...) women were restricted to the translation of religious texts [and] when the work of a woman translator was published, it was often anonymous.

Émilie du Châtelet, portrait by Maurice Quentin de La Tour

Émilie du Châtelet, portrait by Maurice Quentin de La Tour

The Routledge History of Women proposes that, as more women gained access to literacy the 19th century and started to make up for a considerable number of the translators in this period, the craft of the translator grew to be considered humble and menial, as opposed to the perception of the writer as a romantic genius. Of course, these women translated mostly the work of men, and rarely published original work under their own names. A memorable exception to the rule was Julia Evelina Smith (1792-1886), first and only woman to translate the Bible, female suffrage activist and author of Abby Smith and Her Cows, an original piece of fiction and political propaganda.

Bess Myers proposes that our understanding of the act of translating is deeply gendered, and explains how this prejudice affects our perception of translation:

The most famous and highly praised translators of classical texts write with a confident exuberance, often expanding or adding to the original. On the contrary, women translators have tended to approach the original more gingerly, with more careful discipline. When it comes to translating classical texts, women translators are constantly caught in a double bind. If they compose translations longer than the classical texts they translate, the results contain too much of the translator’s [feminine] voice. But if the translations are more succinct than the original texts, the translations become sites of sacrifice and loss.

Emily Wilson, photographed by John Chase at Harvard University

Emily Wilson, photographed by John Chase at Harvard University

Mary Herbert, Countess of Pembroke (1561-1621), is remembered for her translation of Robert Garnier's Marc-Antoine. Polyglot Claudine Picardet was a late 18th scientific who translated papers from Italian, German, English and Swedish into French. In 1722, Giuseppa Barbapiccola's translation of Principles of Philosophy by René Descartes from French into Italian was published.

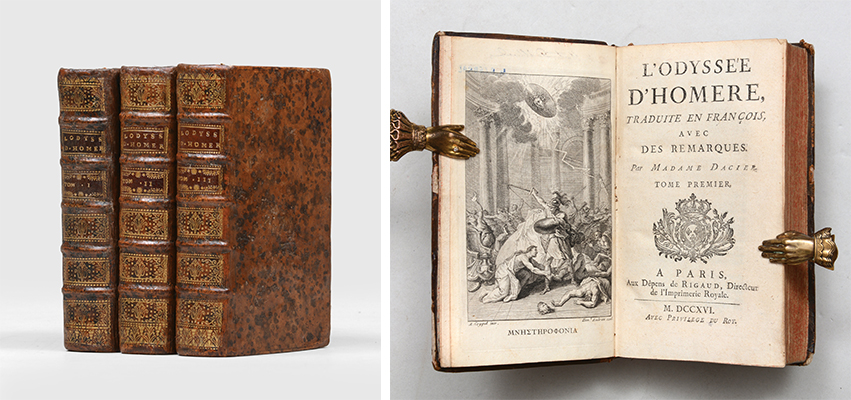

And Anne le Fèvre Dacier (647-1720) wasn't just the first woman to translate Homer's Odyssey—she also affected the French language forever by kick-starting the use of the word traductrice; and is credited with creating a translator's code of ethics. In 2017, Emily Wilson became widely recognized for her own translation of the Odyssey, the first translation into English by a woman. Not only did Wilson make a point to translate the depictions of sexual assault and slave labor from the original text clearly and frankly, without attempts to obscure their violent nature, but she also remarks often the importance of the work of the women who came before her.

To shine a light on the women who paved the way, Marie Lebert compiled a list of thirty female translators from the 16th century onward who are still remembered today; and Bromberg Translations shared a list of eight women who made their mark in history through interpreting, translation and linguistics.

There has historically been a gap between men and women's literacy, and between the male and female authors published, and between the number of men and women translators who earned recognition for their work. Even today, when more women than ever before in history can access education, are allowed to write professionally and be published, and get to translate freely and be credited for their labor; original works by women are still the least translated. Alison Anderson asks, where are the women in translation? She estimates that women make up only 26 percent of the authors published in translation in a given year. In an interview with Monica Manolachi, Helen Vassallo from Translating Women says:

What’s important to note is that if women writers were not translated in the past, it’s not because they weren’t there or weren’t worth being translated—it’s because they were ignored, silenced, or dismissed. (...) The importance of translating women is inseparable from the importance of translation more generally. We need it for a greater understanding between cultures, and if women are left out of culture, then the very notion of culture is itself impoverished.

Portrait of Giuseppa Barbapiccola, engraved by Neapolitan artist Francesco De Grado

And in interview with Literary Hub, David Brookshaw, translator of Mozambican author Paulina Chiziane’s The First Wife, says:

Women writers often give a slightly different focus to the great human themes and dramas that have been the preserve of men writers down the years, and this can result in a more nuanced, and ultimately more rounded depiction of human experience.

Translator Bonnie Huie in her New York home, photograph by Neocha magazine

Translator Bonnie Huie in her New York home, photograph by Neocha magazine

Literary Hub gathered a list of 13 translated books by women that are worth the read, and Words Without Borders offered 9 translated books by women too. In 2017, Words Without Borders interviewed four amazing female translators. In this interview, Jennifer Croft talks about falling in love with the work of women writers and doing the work of approaching authors and publishers to make the translations happen. And Bonnie Huie says:

The Olympics-like vision of world literature, in which authors have come to be seen as representatives of nations, gives rise to literature as product-for-export and self-glorifying national history in quasi-entertainment form, thereby reinforcing institutions in which men tend to be the greatest beneficiaries. There is a vicious cycle for women, as the difficulties do not end upon publication but continue in reception. Gender bias still affects how books are judged today.

The Odissey, translation into French by Madame Dacier, 1716

Women have shaped society and culture all through history, despite the oppressive system trying to suppress female agency and expression. Against the systemic marginalization of women's voices, women have long fought to be heard. Nowadays, women in all fields continue to make strides towards equality, and it's fundamental to foster and recognize the work of women translators.

For International Women's Day, we want to share some noteworthy features. For The Guardian, Alison Flood interviewed ten female translators, who shared the women that inspire their own work. And last year, Book Riot shared six female translators whose work we need to know about. And here are some of the news and interviews that have been shared via ProZ.com Translation News during this past year:

- Staging Translation: An Interview with Larissa Kyzer by Sarah Timmer Harvey

- Experience: I'm a translator for criminals and the voiceless by Lauren Shadi

- Sharon Choi: how we fell for Bong Joon-ho's translator by Phil Hoad

- Wheeler student Jane Josefowicz wins prize for app that pairs refugees with volunteer translators by Madeleine List

- Barbara Moser-Mercer Wins 2020 Danica Seleskovitch Prize for Outstanding Service to Interpreting by Tess MacDougall

Interpreter Sharon Choi by Amy Sussman from Getty Images

If you find an amazing woman translator making the news,

share it at ProZ.com Translation News.