— by Katie Craig (Myanmar Indigenous Community Partners)

Language has long been used as a political tool in Myanmar to include and exclude, to dominate and subjugate, to solidify alliances and to further disassociate from the other.

Despite the significance of language, linguistic diversity is often diminished and brushed past in conversations about Myanmar, even —ironically— conversations about ethno-linguistic diversity.

As such, speakers and signers of the most repressed languages continue to be excluded even in conversations calling for linguistic rights and inclusion of non-Bamar languages.

There are a few ways in which linguistic diversity is minimized that we’ll briefly look at.

Dichotomization of Language Politics

For a long time, the popular discourse on the politics of language (and politics in general) has been framed, on the most basic level, as a dichotomy: Bamar (the most dominant people and language) and non-Bamar. On closer examination, however, it is not so simple. The linguistic (and ethnic) landscape of Myanmar is complicated and multi-faceted, much like the people themselves.

This dichotomization is seen in the way that non-Bamar peoples and languages are talked about. In Burmese, non-Bamar languages are “taing yin thar”, meaning “indigenous” or “native” and usually translated as “ethnic”. Burmese (bama-saka), although by all accounts indigenous to the region, does not receive the appellation of “taing yin thar”.

“Ethnic”

The classification of “ethnic” is a point of resentment among many non-Bamar people. Since the Bamar are also indigenous, it is felt as though the “ethnic” moniker relegates non-Bamar peoples and languages to an ancillary role in a Bamar narrative. The sidelining of non-Bamar languages is seen in other ways as well. Burmese is the language of government and education and the lingua franca in much of central Myanmar (as well as pockets throughout the country).

Even though this has been the popular narrative, reinforced by our language practices, this simplistic dichotomy is not sufficient to understand the power and politics of language in Myanmar, nor its linguistic diversity. Without an understanding of the linguistic diversity in Myanmar we are at risk of further erasure of language and, as language is an essential part of one’s humanity, the people who sign and speak them.

Exclusionist Linguistic Diversity

There is some appreciation (albeit superficial) for the linguistic diversity of the country, though. When asked to further expound upon the “ethnic” languages or peoples (or when confronted with the limited nature of this dichotomous paradigm), many people – local and foreign – will respond that there are seven different ethnic groups: Karen, Kayah, Kachin, Shan, Chin, Mon, and Rakhine. These seven ethnicities correspond to the seven states of the same name, dubbed so by the Burmese (and Bamar-dominated) government.

These categories do not include everyone. They also force many communities into accepting a linguistic or ethnic identity of a more powerful group, sometimes ones with armies. They also gloss over the great linguistic diversity under each ethnonym, further erasing many of the languages of Myanmar. As an additional note, these groupings also encourage the conflation of arbitrary (and often contentious) state lines with a particular ethno-linguistic group – and sometimes particular armies.

Without addressing this erasure, we are perpetuating that which we claim to be fighting against and are not creating an inclusive society where all are represented and given full rights.

Some Questions to Ask

If we say that our objective is complete linguistic human rights for all but deny or ignore those languages (and the people who speak and sign them) that do not fit our narrative, we are working against our stated goal. Just as non-Bamar languages have been made periphery, many languages have been made a periphery to peripheries – or ignored entirely.

As you read and hear about Myanmar in the news (and at our GLAD22 event), keep these things in mind and ask, “Who may be excluded from this? Is this a reductionist take? How can I learn more? How can we ensure that we aren’t erasing languages in our work to achieve greater linguistic rights”?

These questions are also not limited to the Myanmar context. What about in your context? Often we are denying linguistic rights, and other human rights, for some, even while we pursue linguistic rights for others.

You can learn more about language, linguistics, and Myanmar by following Myanmar Indigenous Community Partners (MICP) on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook @MyanmarICP, finding us on our website: myanmaricp.org, and subscribing to our newsletter (you can do that on the website, at the link in our bio on Instagram, or message us with your email on any platform).

You can support us and our work in language rights by sharing —this blog post, our social media channels, and the things that you have learned— with those in your circles. We will have the option to donate soon, keep checking our social media and website!

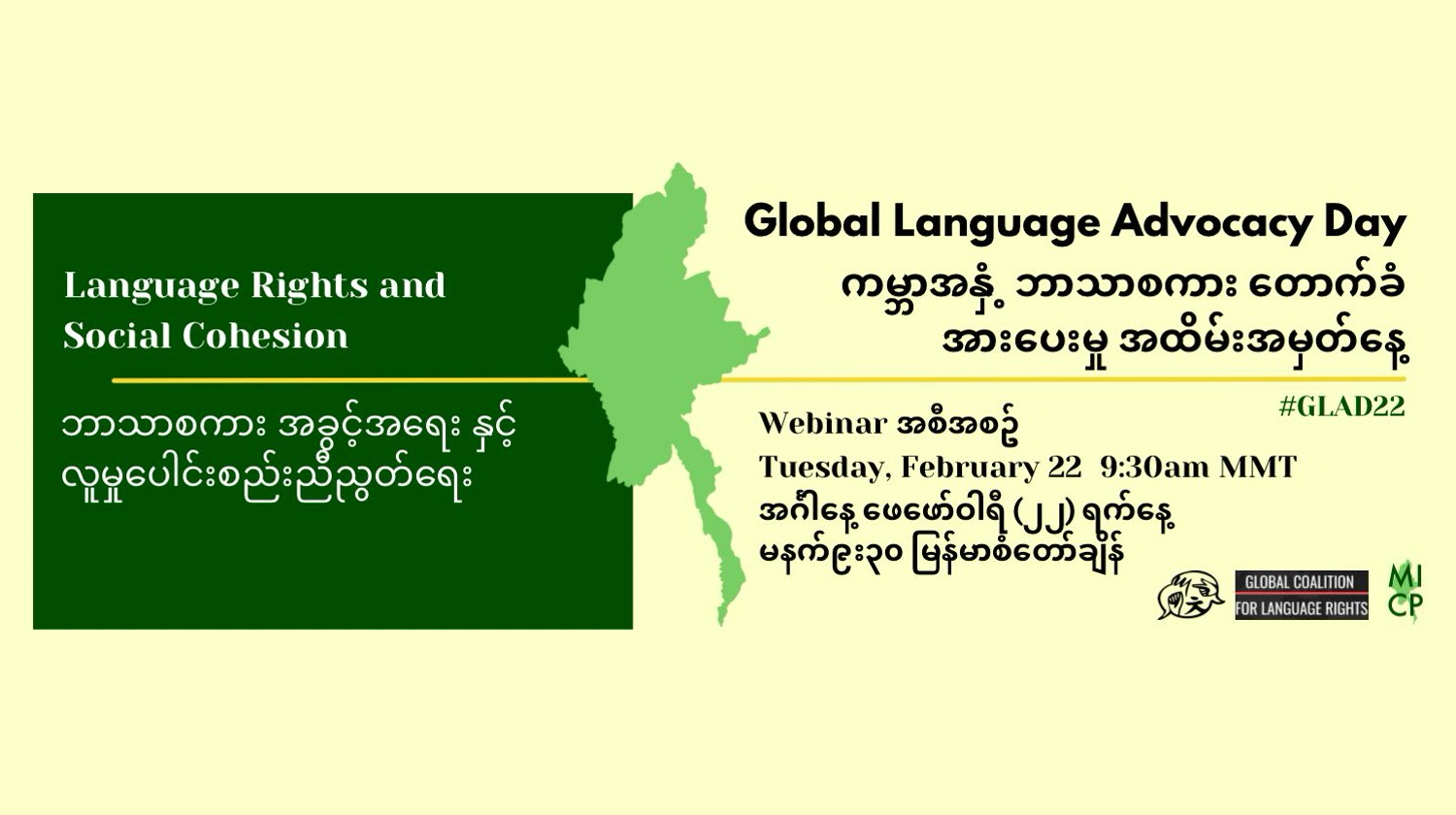

Join us on February 22nd, Global Language Advocacy Day, for a panel on Language Rights on Myanmar! Pre-register here.