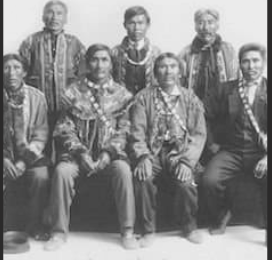

In this week’s Language Watch, we head for the first time to Canada, and the indigenous peoples known collectively as the First Nations. We zoom in on the northern boreal and Arctic regions and on the Dene people, who speak a group of languages that are described as Northern Athabaskan. This prizewinning video is a beautiful introduction to the Dene people and is well worth a few minutes of your time:

One of the several nations who speak Dene are the Chipewyan, whose language is known as Dëne Sųłıné Yatıé, which has nearly 12,000 speakers, mostly in Saskatchewan, Alberta, Manitoba and the Northwest Territories.

Traditionally organised into independent bands, the Chipewyan were nomads who followed the seasonal movement of the caribou. These animals were their chief source of food and of skins for clothing, tents, nets, and lines, although the Chipewyan also relied upon bison, musk oxen, moose, waterfowl, fish, and wild plants for subsistence.

Traditional Chipewyan socio-territorial organization was based on hunting the migratory herds of barren-ground caribou. Hunting groups consisted of two or more related families that joined with other such groups to form larger local and regional bands, coalescing or dispersing with the herds.

The Chipewyan were, and generally still are, animists. Animals, spirits, and other animate beings existed in the realm of inkoze simultaneously with their physical existence Inkoze is a philosophical framework – a way of thinking aand conversing about human knowledge. Humans were part of the realm of inkoze until birth separated them from that larger domain for the duration of their physical existence. Knowledge of inkoze came to humans in dreams and visions given to them by animals or other spirits.

When the Hudson’s Bay Company established a fur-trading post at the mouth of the Churchill River in 1717, the Chipewyan intensified their hunting of fur animals. Members of the tribe also took advantage of their geographic location between the British traders and tribes farther inland, acting as middlemen in the fur exchange by brokering deals with the Yellowknife and Dogrib tribes farther west.

A smallpox epidemic in 1781 decimated the Chipewyan, and subsequent periods of disease and malnutrition further reduced their numbers.

Fast forward to the 21st century, and Canada now has around 1.7 million people of indigenous descent, or just under 5% of the overall population, many of whom live in communities hit by crime, ill-health and poverty.

Complaints about police discrimination are widespread – including a the recent case of Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation Chief Allan Adam and his wife, Freda Courtoreille, who say they were assaulted by RCMP officers in a Fort McMurray parking lot. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has said discrimination by police against indigenous people and people of colour “needs to end”. He spoke after police officers shot and killed an aboriginal woman and video showed police appearing to purposely drive into an indigenous man.

On the linguistic front, Chipewyan was the first Athabaskan language encountered by Europeans in Canada in 1686 at the York Factory trading post, and also the first to be documented. A number of vocabulary lists were put together during the 18th century.

There are a number of ways to write Chipewyan using the Latin alphabet and with syllabics which were devised by English and French missionaries during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

According to the 1996 Canada Census, only 44% (or approximately four out of ten) people in the Northwest Territories (NWT) who learned Chipewyan as their mother tongue now use it as the main language at home. This means that the number of children hearing and learning the Chipewyan language at home is less than half of the previous generation. Use of the language is declining fairly rapidly.

Today there are a number of supporting organizations, agencies and governments that provide support for the Chipewyan language (and many others). Language users and language and culture organizations in Canada’s Northwest Territories collaborate on activities, programs and services. This already occurs in some language communities, but there is considerable room to increase cooperation.

Yet another example of the immense diversity in the world, which nevertheless remains endangered by powerful lobbies, cultures and languages, amid widespread indifference and racism.

Based on research by Jing Wu of Translation Commons

See all entries from this Language Watch series