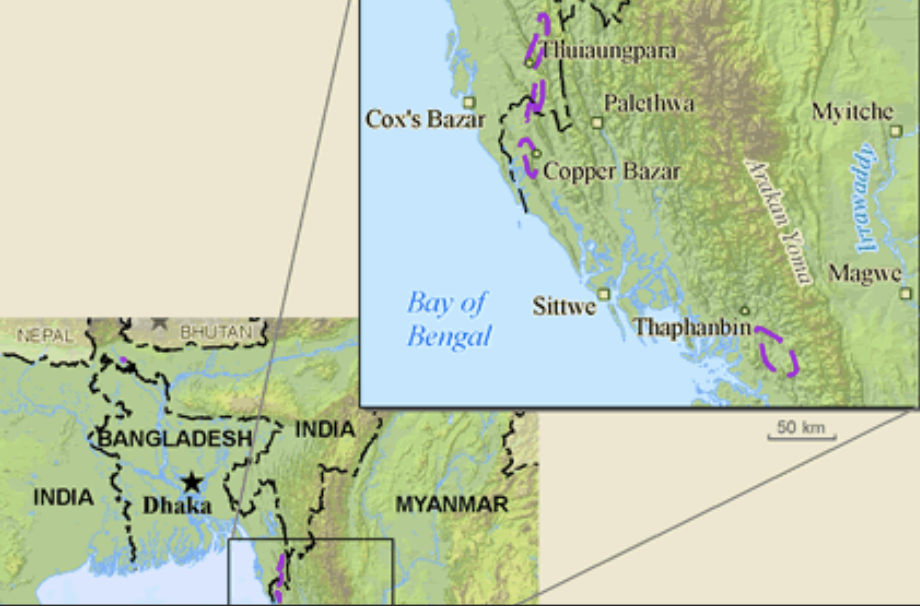

Some of the communities and languages we focus on in this series may be vaguely familiar to you. Many others are completely unknown in the wider world – and barely even recognised or understood in the countries in which they have lived for centuries. Such is the case of the Mru people of Bangladesh – one of the many tribes that populate the Chittagong Hill Tracts, an underdeveloped and heavily militarised region in the South-East of what is already a country facing momentous struggles of its own. Today, around 30,000 Mru speakers live in Bangladesh. Mru populations also exist in neighbouring India and Myanmar, where their situation is just as disadvantaged.

The Mru (Bengalii: মুরং ; Burmese: မရူစာ) are thought to have arrived in the Hill Tracts in the 17th and 18th centuries, mostly from what was then Burma. Some scholars date that arrival back to the 14th century. Given their remote geographic context, the tribal Mru are a very isolated people, exacerbated because of a national policy restricting visitors in the strategic border areas and prohibiting outsiders from obtaining land there.

Since the founding of Bangladesh 50 years ago, the Mru have suffered from the national government’s refusal to grant full citizen status to non-Bengalis. This resulted in a period of virtual civil war in the region, with the military siding mainly with the settlers. Despite the ceasefire in 1997, the Hill Tracts remain off limits to journalists and human rights workers. Regular massacres, rapes, murders and destruction of villages have been documented, and substantial numbers of Mru have fled across the borders into Myanmar and India.

Despite their long existence as a separate ethnic group and their cultural uniqueness, the Constitution of Bangladesh has not recognised them as ‘indigenous peoples’. Rather, the 15th amendment to the constitution, adopted in 2011, has referred to them as “tribes, minor races, ethnic sects and communities” (art. 23A).

Mru culture is distinctive even from other tribes in the same region for a number of reasons. Take for example the birth and death rituals. After the birth of a child, four short bamboos are placed on the bank of the stream. A chicken is then killed in honour of the deities and its blood poured over bamboos tied together. A prayer is then said for the well-being of the child. By contrast, on the death of a Mru individual, their body is put in a coffin made of split coloured bamboos and in some cases rugs and blankets. The body is then cremated, and the remaining unburnt pieces of bones are collected; after being stored in the village for 2–3 months they are stored in a small hut constructed above the location at which the body was cremated.

The men wear Burmese jackets, called "Kha-ok", and a cloth on their heads which leaves the crown uncovered. Mru women are topless before marriage, with the lower part of the body covered by a short cloth. This skirt is woven from yarn, obtained from Indian merchants. Some wealthy women add a string of copper pieces to the string of beads around the waist. They also wear silver earrings, made of hollow tubes about three inches long.

In music too, the culture has distinctive features – the Mru are known for the ploong, a type of mouth- organ made of a number of bamboo pipes, each with a separate reed.

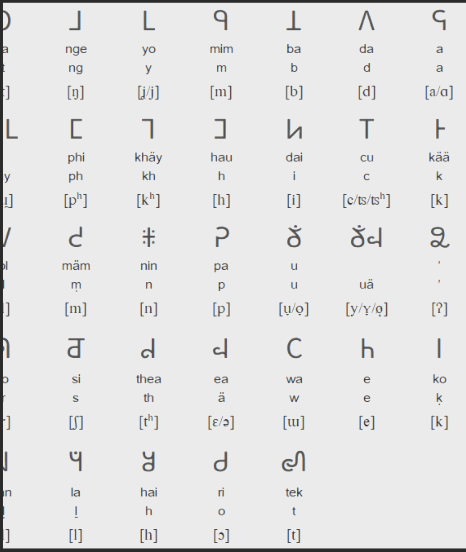

Turning to the linguistic front, the word “Mru” itself means “Human” in this Tibeto-Burman language (part of the Sino-Tibetan language family). Mru is written in both Latin and the Mru alphabet, created in the 1980s by Man Ley Mru, and now understood by an estimated 80% of Mru people The language is considered "Severely endangered" by UNESCO. As in so many other contexts, the language of power (in this case Bangla, or Bengali), is often adopted for the sake of convenience.

Official education in the Hill Tracts is in Bangla, which for many of the region’s indigenous people is not even their second language. The result, coupled with the regional instability, has been a catastrophic dropout rate in government schools and steady cultural erosion among the Mru.

But for you, sitting wherever you are in the world as you read this, what’s your honest response to this. A tragedy, or something entirely natural and even logical? Does the endangering of languages and cultures you’ve never heard of matter? And if so, why?

See all entries from this Language Watch series