Kombo na nga Dachiny, naza mwana ya Congo pe napesi bino banso mbote bisika bozali! Of course you recognised immediately, didn’t you, that this is Lingala, one of the languages of the Congo Republic, and that it means “My name is Dachiny, I'm Congolese and I'm greeting you, wherever you are!” ?

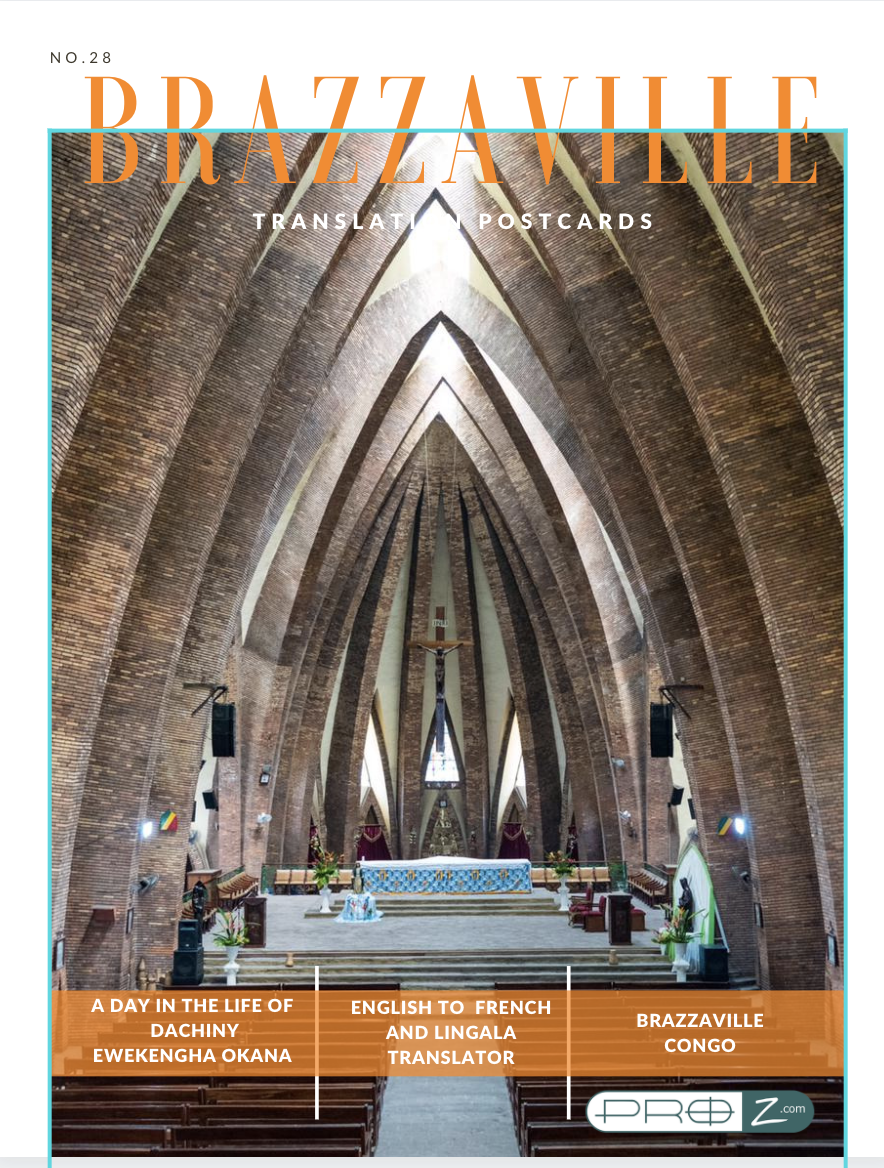

In the same way, you’re perfectly aware that the Congo Republic (or simply “Congo”) is a different country altogether from its much larger neighbour, the Democratic Republic of Congo (once known as Zaïre). The former, once a French colony, has its capital in Brazzaville – named after the 19th-century Italian-born explorer Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza, while the capital of the DRC – formerly colonised by Belgium – is Kinshasa. Interestingly, the two cities, on the right (Brazzaville) and left (Kinshasa) banks of the Congo river, are the closest capitals in the world…

Brazzaville also has the distinction of having served as the capital of Free France at the height of the Resistance to the Nazis in World War II. The Brazzaville Declaration drawn up in 1944 attempted to redefine France’s relationship with all its African colonies, and independence followed in 1960.

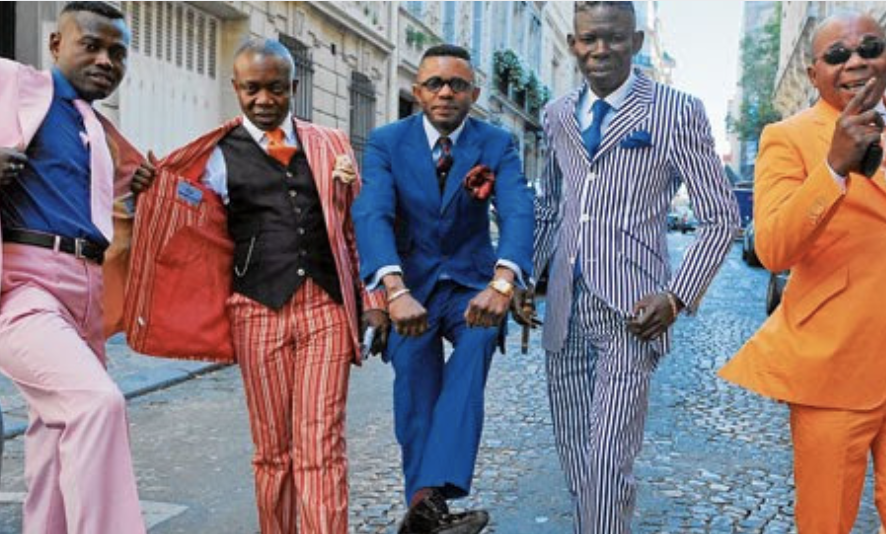

Known to locals as Brazza la Verte on account of its lush greenery, Brazzaville so full of mangoes during the rainy season that you can find them lying on the ground. A city of music and dancing, to such an extent that the weirdest effect of the lockdown is the silence, with no music and no kids playing football in the streets. It’s also the birthplace of a movement that’s become internationally renowned and adopted in many African countries – La Sape. The acronym stands for La Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes (The Society of Ambiance-Creators and Elegant People) and its members are dandies who wear colourful tailor-made clothes that cost a small fortune.

General knowledge lesson over, let’s zoom in on the man himself. Born and bred in the city, the story of how he became an English to French and Lingala translator is really quite extraordinary. On graduating in 2014 from the local university, with a Master’s in English to French Translation – he was under 25 at the time – he discovered to his chagrin that there was simply no work around. Only the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is allowed to carry out legal translations, and the profession is not officially recognised in Congo. In fact, he’s aware of fewer than ten translators in the entire country who make a living from their work.

Given the scarcity of opportunities, there was no other option but to apply to the 5-star Radisson Blu in Brazzaville, where he was offered a job as a receptionist and “night auditor”, which involved doing the books, checking the bills and preparing for the next day. In fact, the monthly salary of €200 wasn’t bad – certainly more than a young teacher would earn, but in Dachiny’s mind it was clear he was not destined to be a receptionist. He wasn’t sure what on earth he was doing at the hotel – he was a translator! So determined was he that he made his way one day to the human resources department and told them what was on his mind: “I’m not a receptionist, I’m a translator. Give me something – anything – to translate. Then you’ll know what I can do.“

The first document he was given turned out fine, and he put aside the extra money he earned from this and subsequent texts to buy a computer – something that was out of the question on his regular salary. Armed with his laptop, he then began to freelance, and one day decided to jump ship and become a full-time translator. One of his favourite sayings is “The most phenomenal success starts with the craziest dream”.

Dream, or no dream, he first had to appease his mother, who expressed her strong misgivings about him leaving his regular job – as mothers do. But it all turned out well in the end. He now earns over eight times his former salary and is in regular contact with agencies across the world. Life, he says, is pretty smooth.

He found his way early on to ProZ.com and now works regularly on translations from English to French and Lingala. Thanks to insights he received from ProZ, he became the country’s first professional subtitler. It all began when he came across a sermon by an American preacher that inspired him. He taught himself to subtitle, so that he could help others benefit from the same message, and then found work with a US agency specialising in AVT. He went on to teach a friend the same skills so that they could collaborate on subsequent projects.

The linguistic situation in the Congo is a complex one. The French used there is identical to that in metropolitan France – and is of course the national medium of education. It’s only the spoken variety which is tinged with local patois. Within the country as a whole, there are hundreds of languages, but only two have official status: Lingala and Kituba, Surprisingly, they are not taught at school – only at University. Less surprisingly, as a result, there are very few translators into either language. Lamenting the low status of Lingala, Dachiny is of the firm opinion that “Language defines a country”. Whenever possible, he interacts with his fellow translators in Congolese, even offering training on the ins and outs of the digital market, so that they can begin to make a change together

Still, there are benefits to this on a personal level. Dachiny is one of very few Lingala translators registered on ProZ. As he’s the only paying ProZ member in the entire country, he naturally appears first in the directory and thus has preferential access to the offers posted there. Many of them come from agencies in countries like Egypt or India – it seems that first they assure their clients they can handle Lingala and then search frantically for someone to fit the bill. Still, they deliver the work, and they pay, so everyone’s happy. Once, that is, they find a way round the logistical challenge of moving money around (PayPal, for example, don’t operate in Congo, although Payoneer is an option). Other obstacles to be surmounted include low local rates, power cuts and the expensive but slow internet connection.

Dachiny doesn’t have a regular starting time, as he likes to sleep late, but also works late – on medical, marketing and general texts, as well as a range of films and TV shows. And he works hard – sometimes so hard that he forgets to eat and has to be reminded. Breakfast every day is an omelette with a cup of black tea – an attempt to diminish his coffee addiction. The main staple in meals is cassava, whose leaves and sticks are both regular ingredients in local fare.

The weekends are devoted to walking round the city, or breaks for some fresh air on one of the islands of the Congo River – as far away as he can get from a screen.

Dachiny remains modest about what he has to offer the community. “I’m not there yet,” he says. But within his story hides a tale of persistence, ambition and success that has plenty to say to all of us.

Dachiny's ProZ.com profile is: https://www.proz.com/profile/2332913

Translation Postcards are written for ProZ.com by Andrew Morris. To feature, drop him a line at andrewmorris@proz.com

This series captures the different geographical contexts in which translators live, and how a normal working day pans out in each place. The idea is to give an insight into translators and translation around the world.

Previous Translation Postcards