It was a humble beginning. One of eleven children, nine of whom are still alive, Thomas Chahweta grew up in a rural village in Zimbabwe. As in many countries in the South, children were seen by the previous generation as an investment. His parents were subsistence farmers and he and his siblings worked hard in the fields growing crops, selling the excess harvest to pay for school fees.

Freak weather events like Cyclone Leon-Eline in February 2000 proved devastating throughout Southern Africa, with houses collapsing while rivers burst their banks and flooded roads. The land was suddenly covered with a carpet of sand, destroying crops. Years of drought followed, with the parents struggling to put food on the table. Still, they worked hard to give their children an education. Thomas finished his advanced level studies at a Tea Estate school, where the students woke up at 4am, spent all the morning picking tea leaves, then got education paid by the Estate from noon till 7pm. They used what little money they earned to buy books and clothes.

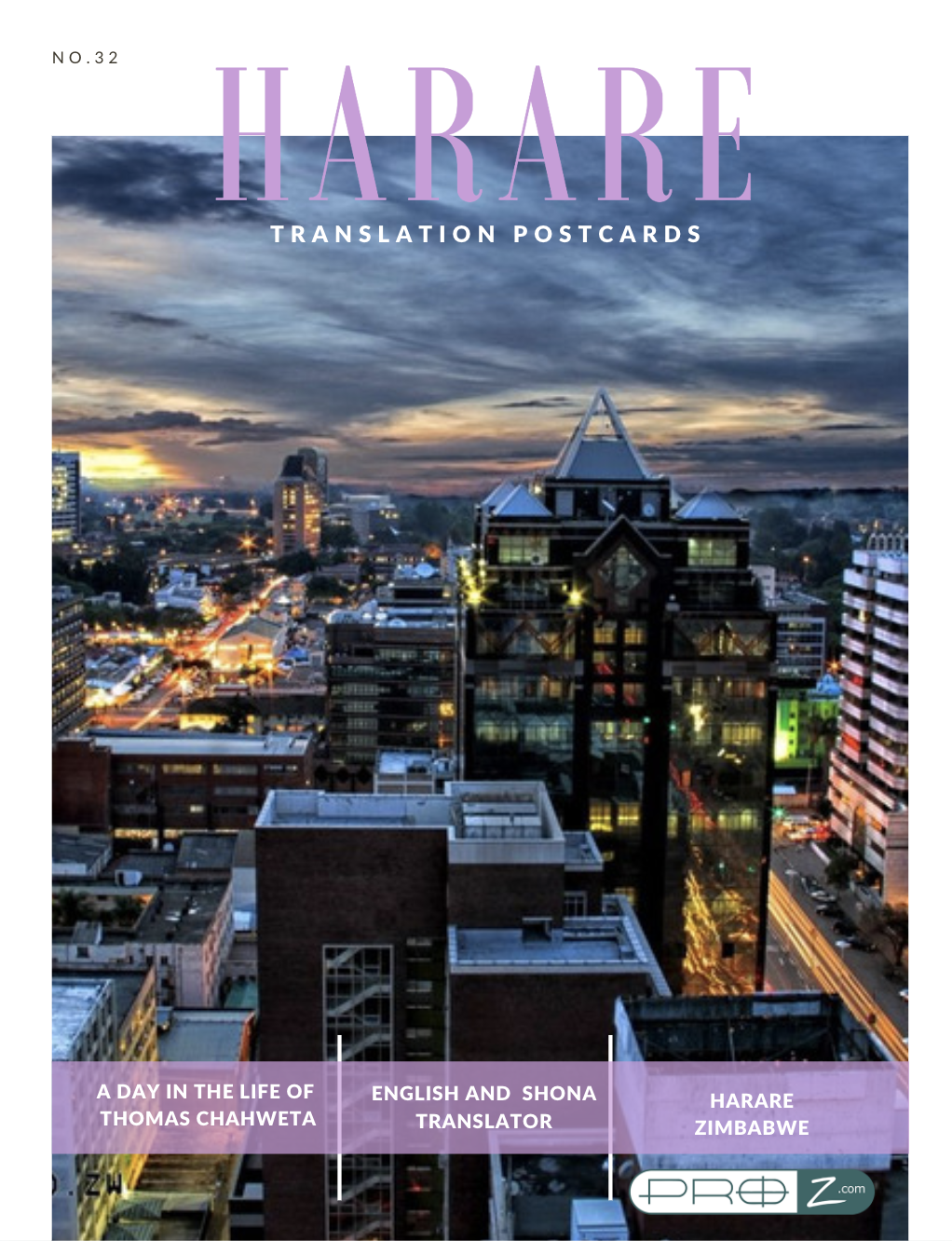

Now, as a translator living in one of the suburban settlements surrounding Harare, Thomas’ life has changed beyond recognition, but we’ll come to that later…

The name Zimbabwe literally means “House of Stones”, after the collection of stone edifices that are the oldest man-made buildings south of the Sahara – some of the walls soaring to over 9m, and made of stones laid upon each other without mortar. The complex, which is now called the Great Zimbabwe, dates back to the 8th century, but with ample evidence of occupation centuries earlier. The country is home to the Victoria Falls and a rich diversity of wild life, the climate is temperate on the plateau and gives rise to lush, fertile landscapes.

It’s a friendly place, where it’s the custom to address older women as “Mhamha (Mum),” as in “Makadii Mhamha? (How are you Mum?)” or “Gogo (Granny)” if they are older. They in turn treat you like their children and they'll call you their sons, saying, “Mwanangu (my child), come here.” And they’ll also not hesitate to discipline you like a mother would. When they notice that something’s been done wrong, they’ll call the culprit out in a direct way that can be quite entertaining – as long as it’s someone else being reproached, not you.

When you go to a funeral, it's the tradition that everybody comes. The family provides for everybody. Just like in the village, anybody can walk in. They will be fed and sing songs and talk about the life of the person. And while it’s a mournful occasion, it’s also a chance to be together. Zimbabweans, Thomas says, are very good at remembering that we all come from smaller groups, be it a tribe or a village or anything like that. “It's unified. We are a family”.

Thomas’ own family has its roots in Mozambique, where his father’s great-great-grandfather Chahweta escaped certain death. Chahweta was the youngest son of his father’s first wife, but when it came to the succession, the children of the second wife planned to kill him. His mother helped him get away and he crossed the border into Zimbabwe in the 1800s. Thomas’s own parents were born in the middle of the 20th century and grew up during the war that led to the overthrow of white rule in what was then known as Rhodesia, leaving school at a very young age due to poverty and the conflict.

When Thomas himself completed school on the Estate, access to higher education was expensive. So he began teaching English, Maths and Shona at one of the local schools. The legacy of Mugabe might be a polemical subject, but one undoubted achievement is that literacy levels are high in the country. Shona is one of Zimbabwe’s three official languages alongside English and Ndebele, although there are also 14 regional dialects. Thomas also learned Swahili by interacting with refugees from East Africa who lived in a nearby camp..png?width=540&name=Screenshot%202021-01-09%20at%2008.25.16%20(1).png)

Meanwhile, his family had become Jehovah’s Witnesses. Thomas was invited to join the translation team at the church’s local branch as a voluntary worker, and underwent translation training for several months. It was as a direct result of that training that he became a translator. Thomas’ term as a volunteer ended after four years, by which time he was translating full time. Buoyed up with confidence, he set out his stall as a freelance translator. After a tip-off from a friend, he discovered ProZ.com, registered and managed to find enough work to buy his first ever computer – an impressive feat in a country where hyperinflation has raged for years.

Meanwhile, he’s also studying electrical engineering at a local college to add another string to his bow. In fact, his timetable involves a week of study followed by a week of translation, but when projects come in, he works round the clock until they are complete – mainly pharmaceutical texts, but also general content, religious texts, health booklets and transcription. Shona is a small language and you have to be prepared to turn your hand to whatever comes your way.

Thomas works only with international clients – all sourced through ProZ.com – as there’s not much local demand. But there are considerable challenges involved in simply getting through a day’s work. Frequent power cuts, expensive internet bundles and great difficulty in getting paid, as PayPal is not supported and the local currency is unrecognized elsewhere. Sanctions have wrought further economic damage over the years. Fortunately there are workarounds, but we won’t go into too much detail here… The rates are low too, but there again, the cost of living is too, so Thomas is not one to complain.

The morning begins with a tea or coffee, with homemade bread. Biscuits with mazoe (a sort of diluted orange crush) follow, and the main dish of the day is sadza – a paste made of mealie meal and water, eaten with fried chicken and vegetables such as the kale-like covo, which is grown everywhere. It’s all eaten with the fingers of course, scooping up gravy as you go. Thomas assures us that while it might be a strange experience the first time, and a few fingers get burned while dipping into the hot goopy mixture, people soon grow to love it.

The weekend is taken up with church meetings or preaching, sightseeing, watching the starry night sky, and the simple presence of nature, a pastime very much in tune with his favourite Biblical quotation: “Lift up your eyes to heaven and see. Who has created these things? It is the One who brings out their army by number; He calls them all by name. Because of his vast dynamic energy and his awe-inspiring power, Not one of them is missing.”(Isaiah 40:26)

Thomas' ProZ.com profile is: https://www.proz.com/translator/2545393

Translation Postcards are written for ProZ.com by Andrew Morris. To feature, drop him a line at andrewmorris@proz.com

This series captures the different geographical contexts in which translators live, and how a normal working day pans out in each place. The idea is to give an insight into translators and translation around the world.

Previous Translation Postcards