On a foggy day, there’s a deep, resonant sound that rolls in from the water: the horns of freight tankers inching their way towards the commercial ports of New York Harbour, through the Narrows. We’re in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, a lower-middle-class district with rich Italian and Irish roots, so you can count on getting phenomenal pizza at Campania, world-class pignoli and cannoli at Paneantico, and a perfect cocktail of whiskey and banter at Kitty Kiernans. But look carefully and you can also make out Greek, Russian and Spanish threads in the local fabric.

The language you hear out on the streets or at the bar is mostly English, but the sounds of Arabic are becoming increasingly common, with a strong Egyptian presence. It’s a pragmatic, turn-of-the-20th century neighbourhood, built on a grid system. Occasionally gritty, with roads that are repaved every couple of years for no apparent reason (although this suits the local construction companies, so best ask no questions) and a lingering memory of Old Europe in the air.

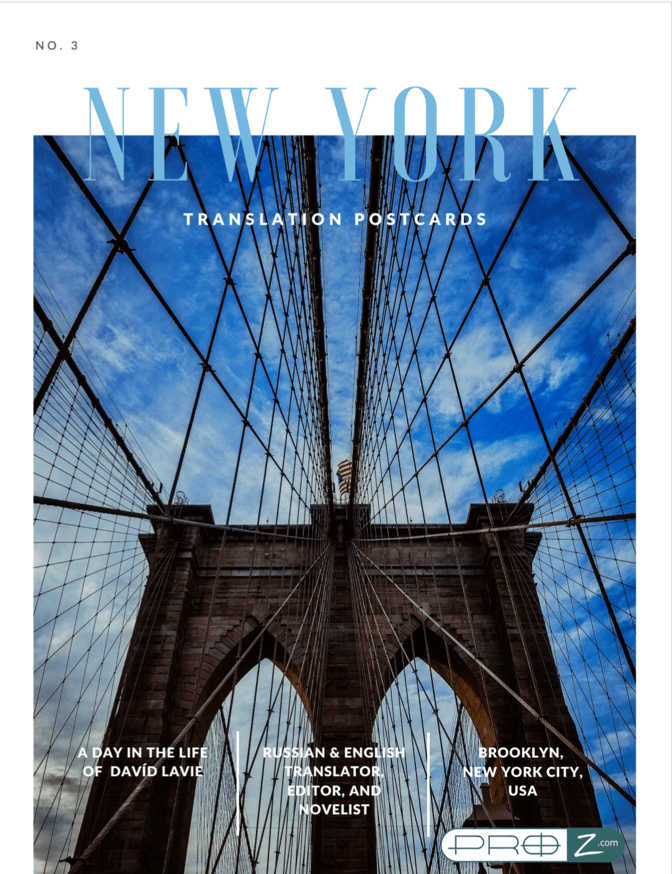

Looming over the skyline is the Verrazzano Narrows Bridge, connecting Brooklyn to the smallest of the 5 sibling-boroughs that make up NYC – Staten Island – and, by extension, to New Jersey. From a bird’s-eye view, the Verrazzano, the longest suspension bridge in the US, links Long Island – a spit of land extending some 200 km into the Atlantic and housing 8 million people, 3 million of them in Brooklyn – to the US mainland.

It’s also home to Davíd Lavie: novelist, playwright, intellectual, blogger… and translator. Davíd is that rare breed in translation circles: the true bicultural. To listen to him, you’d simply never guess he was Russian. His accent is flawless Mid-Atlantic, with just a shade of New York vowels, but when he wants, he can launch into a Brooklyn accent so strong (strawng?) you’d think you’d stepped into in a Scorsese movie.

That’s quite a journey for someone who was born Gennady Pritsker in 1976, into the Jewish community in Odessa, the fabled Black Sea resort city. A young Soviet Pioneer, complete with red kerchief, he’d been studying English intensively since he was 6. His parents had originally wanted to up sticks in 1979, but the fact that they were only able to set out for New York in 1987 gave the young linguist the chance to thoroughly imbibe Russian culture, music, and the rhythms of the language until he was 11, deeply enough for it to remain fascinating even long after the permanent move to the US.

On arriving in New York, he was still young enough to watch cartoons, and so grew up absorbing the culture from a very early age. The only stage he missed out on was nursery rhymes!

Throughout his adolescence, Davíd held on to that attachment to his Russian culture, instinctively translating into Russian anything he saw written or heard in English. By the time he left university, he had been doing this running type of translation in his head for a decade. It was then only a small step towards applying that to finance, law, medicine, and IT later in life. Along the way, he also began to translate poetry: an impossible task, but something he describes as a sacred duty of anyone with linguistic talent and intimate access to more than one great culture.

The pendulum continued to swing between the two cultures – Davíd returned to Russia as a 21-year-old, immediately after university, in a bid to reclaim the language and the culture. To his horror, the citizens of Moscow pointed out that he had a Southern accent, which really stung, and so he worked hard to standardise his pronunciation. He now passes for a Muscovite whenever he speaks – so much so that his own mother has been known to josh him about his accent. To this day, once he identifies any ostensibly offending element, he sets to work on ironing it out; only his dress might mark him out on the streets of the Russian capital.

And today, whenever he wants to return to that mental and linguistic space in which to meet like-minded people and get to philosophise about life, Davíd can turn to a group of Russian-speaking friends close by, while several members of his family still live in the same neighbourhood, within walking distance of each other. Russian literature remains a constant presence in his life.

It was about seven years ago that, preparing for a trip to Israel, the former Gennady decided to adopt the more Hebrew-sounding name of Davíd, (which he pronounces the European way, as in DaVEED). The surname followed that same year – there was no straight translation for Pritsker, a toponymical name, so Davíd chose a name which means “Lion” in old Hebrew and whose sound he found pleasing. It also has the added benefit of meaning “life” in French, bien sûr…

David’s favourite working hours are in the afternoon and evening, sometimes at night. Like so many freelance translators, he works from home, which allows him to cook much of what he eats: a mostly vegetarian diet, with a sprinkling of seafood. Like any self-respecting Russian, he’s a great tea drinker. And between spells of work? A few minutes of stretching every hour behind his desk, on an egg-shaped yoga mat – the perfect place to contemplate his two favourite quotes, one by Albert Einstein: “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler”, and the other by Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr: “I would not give a fig for the simplicity this side of complexity, but I would give my life for the simplicity on the other side of complexity.”

Most of his translation clients are local, based in the US, although in the past the breakdown has been roughly 50/50 between local and international. He sometimes has to help ease Russia-based clients over the mental hurdle that someone speaking to them in impeccable Russian can also translate into impeccable English, but a library of references and samples soon helps dispel the doubts. Being based in NYC makes a great deal of sense for anyone translating into English, of course, and so Ru-En projects account for well over 90% of David’s translation work.

His relationship with ProZ.com goes back a few years, both as a translator and as a project manager. Although his work now frequently involves the editing of manuscripts – a monolingual endeavour, of course, as well as some ghost-writing – it’s in translation that his heart lies. It also pays the bills, especially if you branch into outsourcing, whereas in editing and ghost-writing it’s you the client is hiring, making it far harder to scale up via subcontracting.

Returning to the eternal subject of language learning and culture, Davíd compares his mentality to that of a spy, asking himself: “What would it take for me not to be noticeable, or conspicuous, or to stand out as someone who doesn’t fit in?”

Perhaps there’s something of that drive in all of us who love languages and the cultures from which they spring…

Translation Postcards are written for ProZ.com by Andrew Morris. To feature, drop him a line at andrewmorris@proz.com

This series captures the different geographical contexts in which translators live, and how a normal working day pans out in each place. The idea is to give an insight into translators and translation around the world.

Previous Translation Postcards:

1. Norhan Mahmoud in Cairo

2. Clare Clarke in Norway